8. Machine intelligence Deepens our value as creatives

Creatives struggle to measure and articulate their value, which often causes them to lean on creative trends and tool knowledge as metric alternatives. Worryingly, the fundamental workings of machine intelligence targets these these areas directly, and therefore targets creatives too. Thankfully, machine intelligence helps to deepen our value as creatives, by enabling creative products to better support the deeper levels of our creativity.

For the love of trends

The creative industry has a fascination with trends. Every year, our forums of creative discourse—conferences, award groups, publications, blogs, vlogs, twitter, and more—look back on our collective creative output, and review.1 There are multiple categories of interest, such as the style, form, or genre of a project; its creators or who it was made for; or perhaps the ideas and methodologies behind it.

As work is observed under these attentive eyes, patterns start to emerge. Commonalities across projects become increasingly visible and define-able, which in-turn increases their ability to be packaged, shared, and then adopted into the work of others.

In fact, it’s a process not dissimilar to machine learning…

A value dilemma

But why would creatives choose to adopt trends at all?

Writing in her book “Design: The Invention of Desire”, designer, author, and educator, Jessica Helfand, notes an element of nakedness that the creative industry faces: “Design is, admittedly, an industry that does not require certification. With the possible exception of architecture, the practices that collectively characterize the design professions–graphic design, industrial design, fashion, landscape, textile, interior, and interaction design, among others–do not typically require a license. Which makes everyone a designer. Or, for that matter, no one.”2

These observations starkly contrast creatives against professions such as doctor, lawyer, pilot, or teacher; Roles that not only require certification to practice, but that also typically require certifications be maintained. Without similar for creatives, trends can serve as an alternative kind of license…one that affirms a creative practice meets current and contemporary standards.

However, certified professions and commercial creativity aren’t entirely comparable. Where a commercial pilot’s license signals someone’s ability to follow the same protocols and procedures expected of all pilots, creative sameness isn’t quite valued in the same way. By adopting trends, creatives navigate a fine line between contemporary and copy.

Helfand continues, “… design has become a curious commodity. Is it a process or a practice? A product or a platform? And if, arguably, it defies such easy classification, then who wants it and needs it, produces and consumes it?… As the boundaries between professions becomes more porous and the defining characteristics of design expand and proliferate, it has never been easier to call yourself a maker. Everyone has a website, a blog, a ‘brand’—making design as a concept at once more accessible and conceptually less unique. If everyone’s a designer, why hire a designer?”2

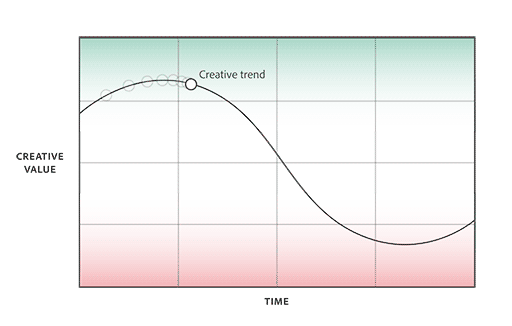

As understood by Helfand, the creative industry has a value dilemma. Where trends can stand as a benchmark for value, an oversubscribed trend can in-fact devalue. This loss in value is important to observe, because it suggests that trends live on a value curve. As a certain style or idea is increasingly co-opted, the curve slopes down. By that same logic, the curve therefore experiences its highest peaks when work appears new and original… a sentiment echoed by creativity psychologists Paul Paulus and Bernard Nijstad: “Creativity is therefore often defined as the development of original ideas that are useful or influential”.3

A return to “techne”

This is all well and good. But originality, usefulness, and influence are problematic as objective measures for creative value. In-part, because the dynamic nature of this trend value curve proves these measures are actually subjective. Trends that start as original, useful, and influential can quickly become unoriginal, useless, and insignificant once they’re perceived as “overused” or “no longer relevant”.

In the pursuit of value, creatives may find that they’re able to consistently seek, identify, and apply trends that land on high points of the value curve. Some may even create work that fuels new trends altogether. In both cases, however, value isn’t attributed to the creator as much as it is to their work. As a result, portfolios typically serve as the de facto container for a creative to communicate a body of “valuable” work by measure of current standards.

But how then, if it’s not solely through their work, do creatives try to communicate their own personal value? We return to the concepts of “techne” and “epistime”—“What creative tools do you use?” “What’s your creative process?”

The language gap as creative value proposition

While contemplating “The Death of the Artist” in The Atlantic in 2015, William Deresiewicz reminds us that, “Art itself derives from a root that means to ‘join’ or ‘fit together’—that is, to make or craft”. With reference to craftspeople from the late Middle Ages, he also describes a historical value model for creative makers: “Creativity was prized, but credibility and value derived, above all, from tradition… Individual practitioners could come to be esteemed—think of the Dutch masters—but they were, precisely, masters, as in master craftsmen.”4

Deresiewicz goes on to examine how changes in culture have shaped the role and presence of artists over time. But this early insight, where a craftsperson’s value is attributed to their mastery of tools, will likely resonate with current creatives who are familiar with the language gap.

Today, our creative ability to become fluent in the language of the tool makes us translators of the language gap. In this role, our creative value is that we speak a language many others can’t. Our frequent journeys back-and-fourth across the gap, executing creative intent through routine sequences and tasks, are the evidence and measure of our personal creative value.

“We shape our tools, and thereafter, they shape us”…and also our value…5

Devalued and replaced

But hold on for a second. Does this fit the narrative of machine intelligence and the next creative wave? If a creative’s value is actively supported by the existence of the language gap, but machine intelligence is actively working to narrow that gap while also democratizing the language of tools in the process, then how can machine intelligence be seen as anything but a threat to creatives? Are creatives about to lose a defining source of their value?

Maybe this is an argument in favor of trends becoming more important than ever for creatives. But hold on for another second… Machine intelligence delivers algorithmic abilities at spotting patterns in our creative content and workflows via datasets; All for the purposes of replicating, iterating, and automating the patterns it observes. Comparing this behavior to the ways creatives define and adopt trends within their work, the similarities are undoubted.

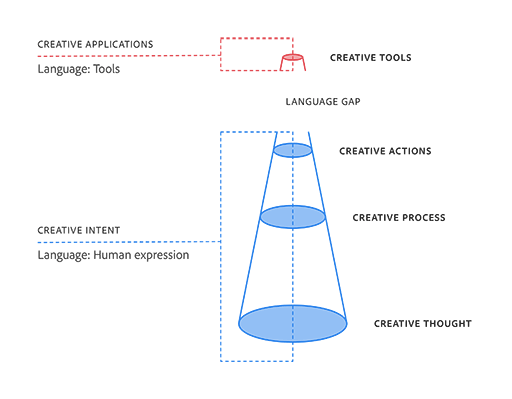

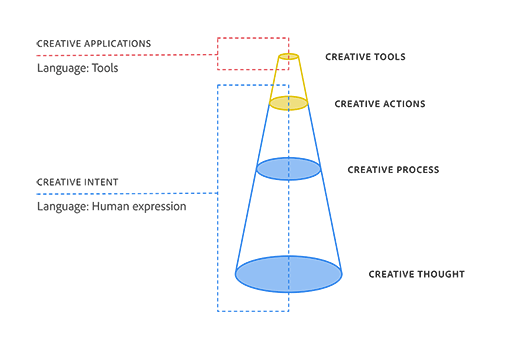

When the language gap was first introduced in this essay series, it was contextualized as part of a creative funnel. At the top of the funnel, creative tools are separated as the primary focus area for today’s creative applications. Moving across the gap, the funnel grows deeper and wider, touching layers that speak to our human creative intent: our actions, processes, and creative thought.

If two primary measures of a creative’s value are drawn directly from the first two levels of this funnel—from their mastery of tools, and their sequencing of actions to produce work that meets current trends and standards—then machine intelligence is poised to severely impact both. Roles such as production designer, layout artist, typesetter, in-between animator, or commercial illustrators and photographers who are primarily trend-driven, are all potentially going to struggle to maintain their value alongside machine intelligence.

However, this impacts all creatives, not just those with particular roles. So, what happens next?

Deeper value: The full impact of machine intelligence

In early 2019, HBO’s satirical news, politics, and current events program, “Last Week Tonight with John Oliver”, explored the subject of automation. In particular, the piece unpacked key technology shifts occurring across industries and their resulting impacts on employment. After recognizing both challenges and benefits, Oliver headlines “The one thing that we know for sure is, automation is not going to stop… [we should] be preparing the next generation for the possibility that they may need to be more flexible in their career plans”.6

In the segment’s close, Oliver speaks directly with a group of children, describing to them what this next generation skillset might look like in practice. What he shares sounds curiously creative: “…a series of non-routine tasks that require social intelligence, complex critical thinking, and creative problem solving”.

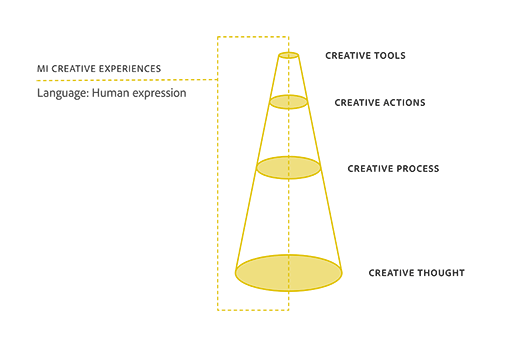

There’s a surprising richness to this description that feels directly relevant to the deeper levels of the creative funnel. These levels are the spaces where we pursue our creative ideas, bring perspectives to our thinking, examine and scrutinize problems via process, and iterate our concepts, responses, and solutions in dialogue with both ourselves and with others. They’re spaces that have been harder to reach with our current creative tools, because of the language gap and the measures of value creatives have built out of it.

It’s in these spaces that we find the full impact of machine intelligence on creative tools and creativity:

- By narrowing the language gap, our vocabulary of tools is able to evolve into a semantic language of our creative intents.

- As this occurs, a unified creative landscape begins to emerge, where siloed disciplines are reshaped into more open and accessible regions of creativity, and where our processes are given more room to expand.

- Supporting these transformations, new flexibility in assets and file formats—as well as the technologies powering them—start to shape creative tools and materials into meta environments for creative systems.

- Here, creatives grow in their capacity to define, explore, shape, and visualize their ideas; navigating different creative modes all from within the same project or collaboration—like a musician who can simultaneously be the composer, conductor, player, and listener.

But ultimately, machine intelligence helps to deepen our value as creatives. By supporting the series of paradigm shifts outlined across these essays, machine intelligence offers creatives greater access to the deeper levels of their creative intent.

Drivers of change

What drives creative change? In the opening essay to this series it was argued that, with the help of tech innovation, creative tools do. But in the next creative wave, if tools do grow into the kinds of creative experience platforms that machine intelligence suggests is possible—perhaps creative change will be most driven by our ideas and how well we explore them.

In a space like that, what would you create?

Further thinking

Ask yourself or discuss with others

- What do you think the current role of trends and tool knowledge is in our creative culture? Do you agree or disagree with the picture painted in the piece?

- How do you try and articulate your value as a creative to others?

- Are you concerned about the ways machine intelligence can replicate and automate things we do in our creative tools today? Do you think that reduces the value of creatives?

- How do you imagine a creative tool that works at the deeper levels of the creative funnel shown in Figure 2? What kinds of projects would it help you create?

References

- “Trends of the Year 2020.” Creative Review, 18 Dec. 2020, creativereview.co.uk/landing-page/trends-of-the-year-2020/. Accessed 30 June 2021.

- Helfand, Jessica. Design: The Invention of Desire, Yale University Press, 2016, p. 22.

- Paulus, Paul B., and Bernard A. Nijstad. “Group Creativity: Innovation through Collaboration.” Oxford Scholarship Online, Oxford University Press, 2003, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195147308.001.0001. oxford.universitypressscholarship.com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195147308.001.0001/acprof-9780195147308. Accessed 30 June 2021.

- Deresiewicz, William. “The Death of the Artist-and the Birth of the Creative Entrepreneur.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 2 Feb. 2015, theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2015/01/the-death-of-the-artist-and-the-birth-of-the-creative-entrepreneur/383497/. Accessed 30 June 2021.

- “We Shape Our Tools, and Thereafter Our Tools Shape Us.” Quote Investigator, 13 Dec. 2018, quoteinvestigator.com/2016/06/26/shape/. Accessed 30 June 2021.

- “Automation.” Last Week Tonight with John Oliver, performance by John Oliver, season 6, episode 3, HBO, 3 Mar. 2019, youtube.com/watch?v=_h1ooyyFkF0. Accessed 30 June 2021.